Today, I woke up and turned on the coffee pot and the turned on the stove to make breakfast. I fixed my food, ate it, and then took a shower. All of this I did effortlessly, relying on my electricity and heat to take feed and clean me. Then, I went to finish my major final project of the semester.

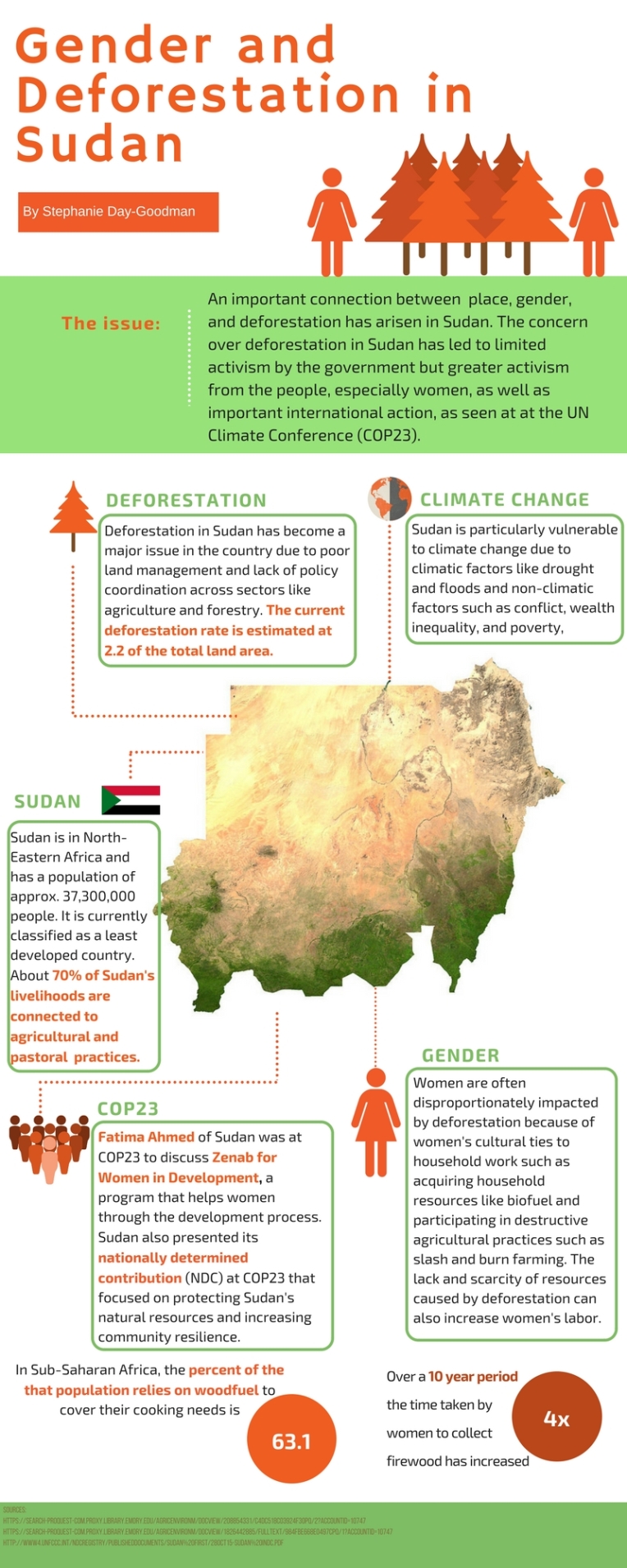

For the past month, I have been researching and writing about women’s response to deforestation in Sudan. Sudanese women are disproportionately negatively impacted by the ramifications of deforestation and are now demanding a voice in legislative and communal matters surrounding deforestation.

Firewood accounts for seventy-percent of Sudan’s energy budget. As a result, the reliance on firewood as well as increased unsustainable agricultural practices, have caused Sudan to have a deforestation rate of 0.84 per annum.

In Sudan, women are often responsible for running the household, including gathering fuel. When there is less fuel available, they are forced to go further distances and carry more fuel or use a different, less healthy fuel such as dung. The forest is also an important commodity for women. Selling wood, fruit, leaves, or gum at market are some women’s primary means of support. The forest is also sometimes the closest and best source of water for rural Sudanese women.

When I woke up this morning, I was able to go through my schedule effortlessly. However, as I was writing this report, I thought of what it would be like to start my day going into the forest to gather enough wood to cook breakfast and warm water for a shower. The labor would intensive.

I am lucky enough to live by a nature preserve; however, what if I did not? What if I lived several miles away from the closest forested area? What would my quality of life and opportunities for success be if the majority of my time was collecting wood?

I know I would not be in college and I know I would be spending the majority of time creating a secure household for my family in which everyone is warm, clean, and fed. Every stick I burned would be precious as it would mean I was that much closer to going to find more forest. Female wood-gatherers in Sudan also report finding wood is dangerous. Not only are they spending immense amounts of time finding wood, they are also putting their life in danger doing so.

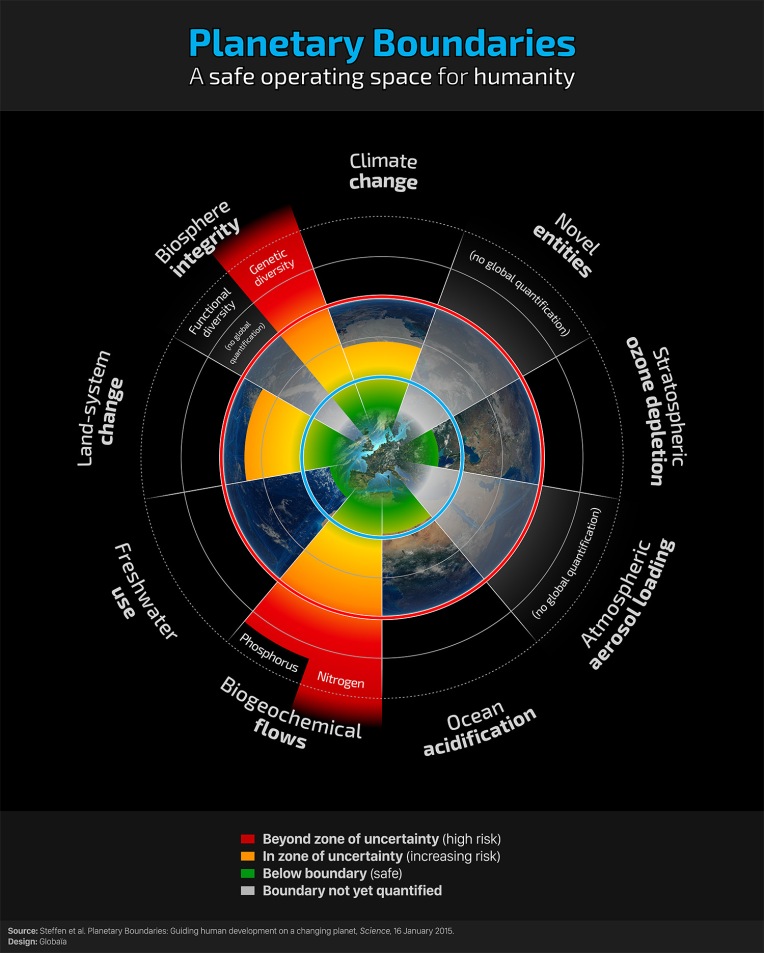

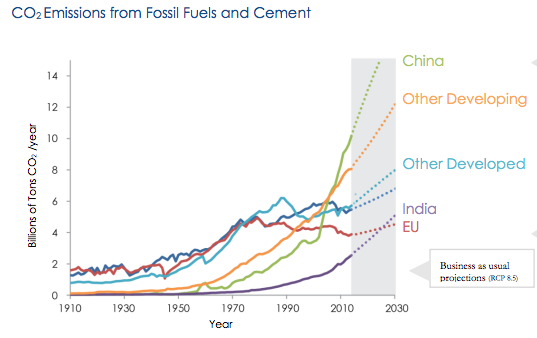

I wanted to visualize this experience on my blog because I think it’s important to think about what we have as well as what we can. Greenhouse gases may originate in one place, but they impact the whole world. I have not felt the ramifications of climate change nearly as much as someone who is reliant on the forests for their livelihoods; however, my greenhouse gas output impacts us both. I have just been fortunate enough to not feel immediate effects.

The positive aspect of this project was learning that there are initiatives to help women build resilience to the effects of climate change. My favorite is Zenab for Women in Development. Zenab uses a multi-dimensional approach to advocate and empower women and girls through intersecting issues such as education, climate change, and health. This year, they were the recipients of a Momentum for Change award for ‘Women for Results.’ I encourage you to see their website and learn more about all the ways they’re making a difference in Sudan.

This semester in this class has been such a whirlwind but it was amazing to be able to take time to research this topic. I hope all of you have learned something from this post, and please take a look at the infographic as well as my final paper, below.

Thank you for reading!

Stephanie